Psychodrama

This month, I attended two events designed to help me develop my skills in facilitating psychodrama.

The first was a weekend retreat sponsored by The Crucible Project. Here’s some more information about the organization as taken from their website:

Focus:

The Crucible Project aims to create a world where people live with integrity, grace, and courage, fulfilling their God-given purpose.

Method:

They achieve this through transformational retreats, groups, and coaching, fostering communities where people live authentically and with integrity.

Retreats:

These retreats are designed to challenge individuals to take a hard look at their lives, wrestle with God, and discover new truths about themselves, finding freedom to break away from self-sabotaging beliefs.

Intense Experience:

The Crucible Weekend is an intense experience that can be emotionally, spiritually, and physically challenging.

Radical Honesty and Grace:

The retreats emphasize radical honesty and grace, creating a space for individuals to wrestle with God and discover new truths about themselves.

Community:

The Crucible Project fosters a community of men and women who have gone through the retreats, providing support and encouragement.

Locations:

The Crucible Project has retreats in the United States, International locations, and Second-level Weekends.

Vision:

Their vision is a world of men and women who live with integrity, grace, and courage.

Mission:

Their mission is to ignite personal change in men and women through experiencing Jesus, and taking a journey of radical honesty and self-reflection.

The retreat I attended was held in Empire, CO, about an hour west of Denver, at the Easter Seals Rocky Mountain Village facility. Most of the meetings were held in a lodge, and we stayed in cabins with other men. There were 37 participants and about that same number of staff members. (In the photo, I’m kneeling in front, second from the left.)

The second event I attended was a one-day Guts Work Facilitation Training held in Taylorsville, UT. It was held at the home of a man who was willing to host it free of charge. Eleven of us were in attendance, men who had previously participated in the Mankind Project NWTA weekend. Three were staff members, and the other eight of us were attendees.

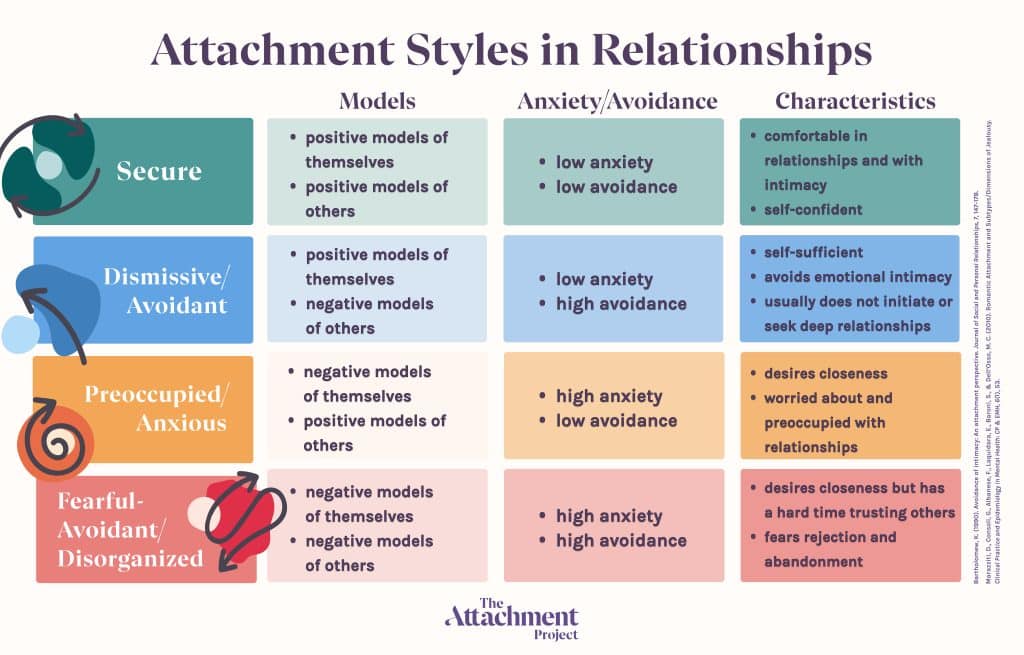

I’ve had a lot of talk therapy over the years with various counselors, which has been great, and I’ve needed it. However, this approach was different in that it was more experiential, somatic, and physical. It aligns well with a book I recently studied called “The Body Keeps the Score” by Bessel van der Kolk. The central premise of the book is that trauma profoundly impacts the brain and body, leading to physical and emotional dysregulation, and that healing trauma requires understanding and addressing these physiological and neurological changes.

One of the main processes used to heal these wounds is psychodrama. Psychodrama focuses on a person’s real-life experiences and internal conflicts, allowing individuals to explore and express their emotions and experiences through dramatic action. While it can be used in individual therapy, psychodrama is often conducted in a group setting, where participants can act out scenes from their lives under the guidance of a trained facilitator. Put together, then, a psycho-drama is quite literally a “drama of the mind and soul.”

In each psychodrama process, I was able to re-enact a painful experience from my past. The result of the process is that I’m able to receive closure and resolution. Technically I don’t actually change what happened in the past, but I’m able to change how I feel about what happened. This results in greater peace and freedom.

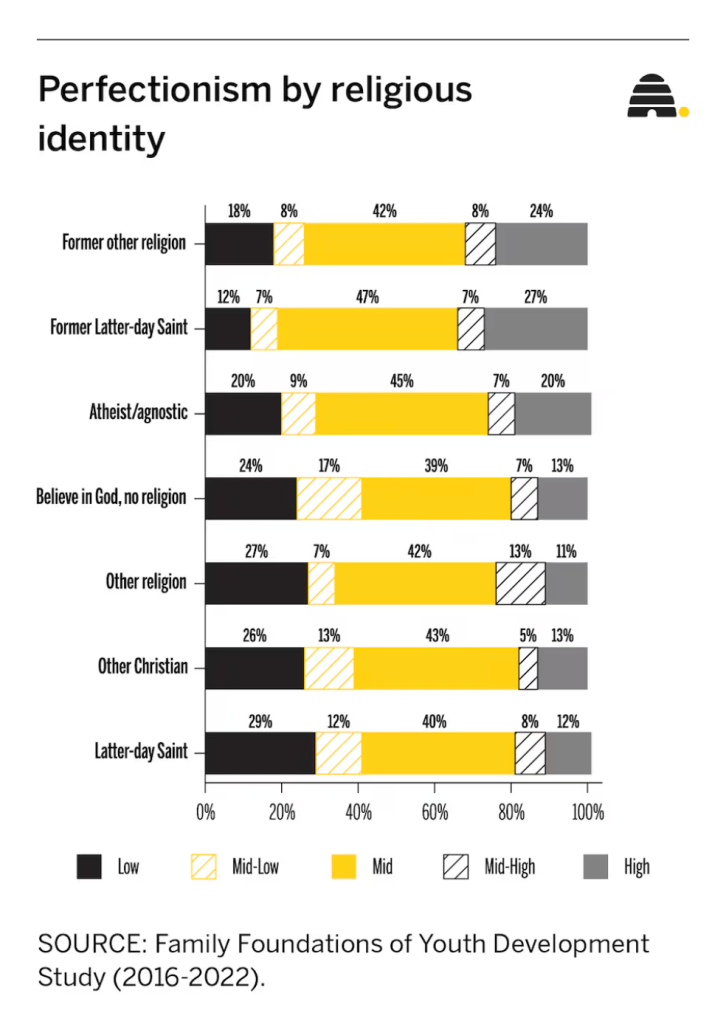

Some of my perfectionist tendencies are the result of experiences I had as a kid, where I felt like I needed to be perfect in order to be acceptable. Of course, perfection in this life is impossible, so that created a lot of internal chaos. Working through the scenarios as an adult showed me that those expectations were unrealistic. I can approach myself with kindness and curiosity. I’m better able to give myself grace.