Let Your Light Shine

One propensity of perfectionists is that we care a lot about what other people think of us. In her book, The Gifts of Imperfection, Brené Brown talks about the 4P’s: pretending, performing, pleasing, and perfecting. These have definitely been part of my inclination, whether consciously or subconsciously.

In this month’s Come, Follow Me, we read about how Martin Harris asked Joseph Smith to let him take the 116 pages of manuscript translated from the first part of the Book of Mormon. Martin lost them and Joseph was chastised for giving in to peer pressure, or “the persuasions of men.” “You should not have feared man more than God.” (D&C 3:6-7) So if I care more about what men want than what God wants, then I’m in good company, with Joseph.

My patriarchal blessing talks about me being a messenger of the gospel, that I should be a good example, and that those in my community would see my example and glorify God. This aligns with Jesus’ admonition to “Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven.” (Matt 5:16)

So, it is good to do good, and to let others see our good examples. But we are also told to “Take heed that ye do not your alms before men, to be seen of them.” (Matt. 6:1) This seems contradictory. Should I let others see me doing good, or not?

I’ve come to the conclusion that what makes the difference is: the condition of my heart. If I perform, or do alms, or good works—with the intent to be praised of men, then my heart isn’t in the right place. If I do good deeds out of the goodness of my heart, then I’m not desiring praise and recognition.

I recently finished a book by Virginia Hinckley Pearce, A Heart Like His: Making Space for God’s Love in Your Life. I really like this quote from Chapter 4.

Learning to live with an open heart is not about learning to say the right words and refraining from saying the wrong words. In fact, just the opposite. I would venture to say that when my heart is open and filled with God’s love, I cannot say it wrong, and when it is hardened and closed to Him, I simply cannot say it right, no matter how carefully I may choose the words or phrases or inflections of voice. Remember that this is all about becoming, not doing or saying.

So, that’s what makes the difference. If I perform or serve with an open heart, then others will see that I am doing it in an authentic, genuine way.

For me, this is really difficult to do consistently. In fact, I’m just coming to understand some of this. A good friend told me that I tend to act and make decisions too often above the neck—meaning that I need to be less analytical and more heart-directed. He’s right. My mind cares more about how I appear to others. Man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord looketh on the heart. (1 Samuel 16:7)

To be continued . . . with Part 71

Imagine yourself in a room, a very dark room with only a small amount of light visible—just enough to make out the outlines of some furniture and the walls around you. You can tell the room is in disarray. There is a couch haphazardly shoved into a corner with the cushions spread everywhere on the floor. Two chairs are overturned and a table with some legs missing is lying upside down in the middle of the room. A floor lamp with its shade missing is propped diagonally against the wall.

Imagine yourself in a room, a very dark room with only a small amount of light visible—just enough to make out the outlines of some furniture and the walls around you. You can tell the room is in disarray. There is a couch haphazardly shoved into a corner with the cushions spread everywhere on the floor. Two chairs are overturned and a table with some legs missing is lying upside down in the middle of the room. A floor lamp with its shade missing is propped diagonally against the wall.  Now, you wonder what more you can do, but then a thought strikes you. I could get a new table, those other walls could use some beautiful pictures, perhaps I could add a vase with flowers and perhaps some new chairs. And on and on this could go. Every time you report, you are given more light and told to clean again. Pretty soon you’re knocking out walls, and adding wood floors, and upgrading the rug and furniture. You are filled with a vision of what the room could someday be and you find fulfillment and purpose in adding to and improving it.

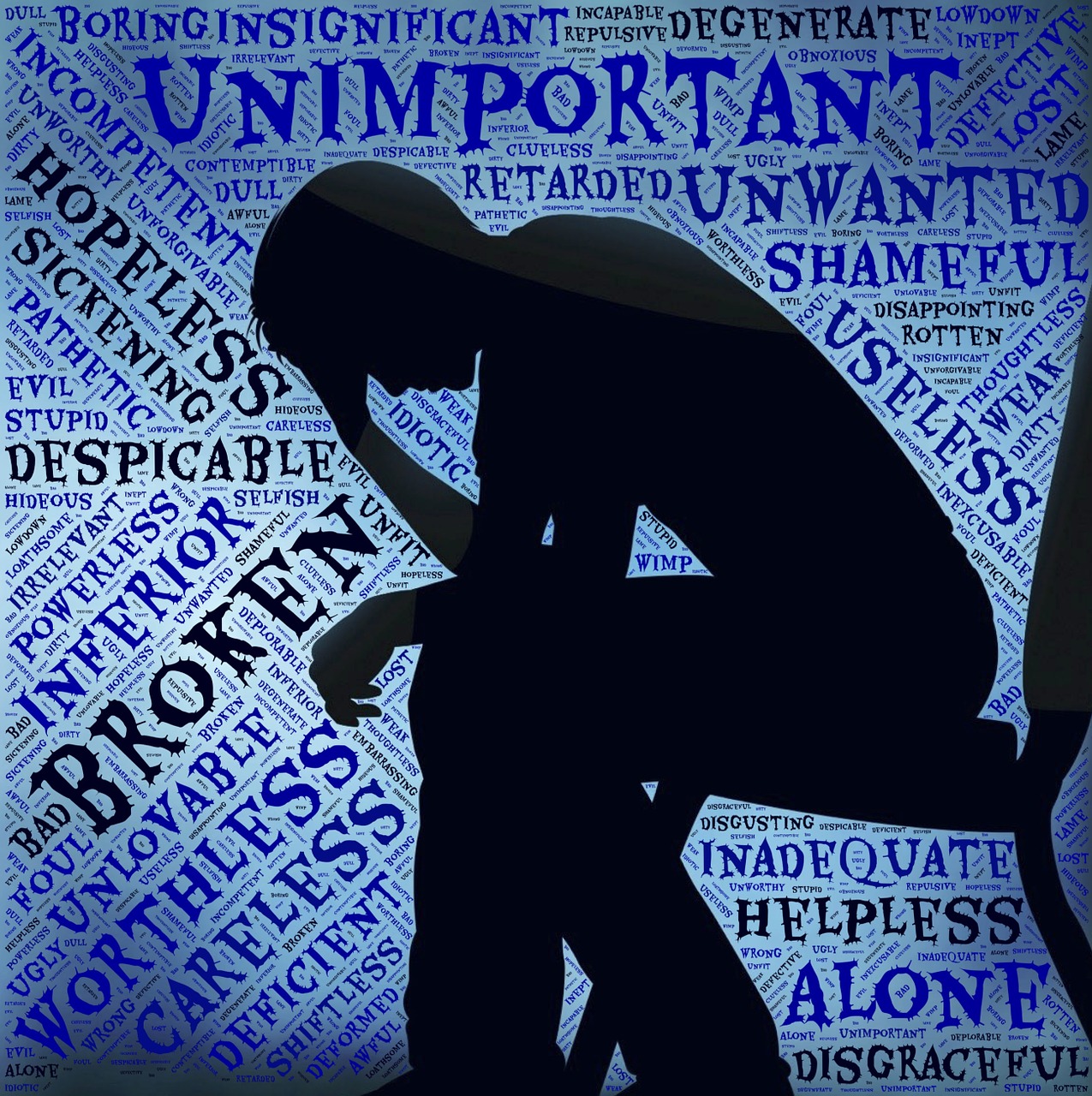

Now, you wonder what more you can do, but then a thought strikes you. I could get a new table, those other walls could use some beautiful pictures, perhaps I could add a vase with flowers and perhaps some new chairs. And on and on this could go. Every time you report, you are given more light and told to clean again. Pretty soon you’re knocking out walls, and adding wood floors, and upgrading the rug and furniture. You are filled with a vision of what the room could someday be and you find fulfillment and purpose in adding to and improving it.  The inner critic—that nagging inner voice—judges, criticizes, and demeans me. Over time, it damages my self worth and takes a toll on my soul. This destructive chatter is fueled by shame and faulty core beliefs—ultimately by the enemy, the father of lies.

The inner critic—that nagging inner voice—judges, criticizes, and demeans me. Over time, it damages my self worth and takes a toll on my soul. This destructive chatter is fueled by shame and faulty core beliefs—ultimately by the enemy, the father of lies.  Again from

Again from  When he looked at people, it was like He could see everything about them. Even though his atonement was in the future, He seemed to know all about them—their struggles and challenges. And he was full of mercy and compassion.

When he looked at people, it was like He could see everything about them. Even though his atonement was in the future, He seemed to know all about them—their struggles and challenges. And he was full of mercy and compassion.  I watched the first season free online. I was so impressed that I made a donation to the cause. I also purchased the DVD set of Season 1, which helps them fund Season 2. I noticed at Deseret Book that the DVDs were in the #1 Bestseller spot on the shelf.

I watched the first season free online. I was so impressed that I made a donation to the cause. I also purchased the DVD set of Season 1, which helps them fund Season 2. I noticed at Deseret Book that the DVDs were in the #1 Bestseller spot on the shelf.  The religious scholars—who conducted the study at BYU—found that religious young adults experience better or poorer mental health as it connects to their belief in grace or in legalism. They surveyed 566 young adults at BYU (most of whom are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) and found that when these young adults believe more in grace and less in legalism, they experience less anxiety, depression, shame, religious guilt, and perfectionism. They also found the opposite: When young adults have a more legalistic view of God, they experience poorer mental health “because it interrupts [their] ability to experience grace.”

The religious scholars—who conducted the study at BYU—found that religious young adults experience better or poorer mental health as it connects to their belief in grace or in legalism. They surveyed 566 young adults at BYU (most of whom are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) and found that when these young adults believe more in grace and less in legalism, they experience less anxiety, depression, shame, religious guilt, and perfectionism. They also found the opposite: When young adults have a more legalistic view of God, they experience poorer mental health “because it interrupts [their] ability to experience grace.”  No matter how hard we work, no matter how much we obey, no matter how many good things we do in this life, it would not be enough were it not for Jesus Christ and His loving grace. On our own we cannot earn the kingdom of God, no matter what we do. Unfortunately, there are some within the Church who have become so preoccupied with performing good works that they forget that those works—as good as they may be—are hollow unless they are accompanied by a complete dependence on Christ.

No matter how hard we work, no matter how much we obey, no matter how many good things we do in this life, it would not be enough were it not for Jesus Christ and His loving grace. On our own we cannot earn the kingdom of God, no matter what we do. Unfortunately, there are some within the Church who have become so preoccupied with performing good works that they forget that those works—as good as they may be—are hollow unless they are accompanied by a complete dependence on Christ. Unfairness is all around us and it is troubling. If we’re not careful, the appearance of unfairness may cause us to reject the favorable along with the unfavorable. Or to use an idiomatic expression, “to throw the baby out with the bathwater.” Perceived unfairness deals us a major body blow.

Unfairness is all around us and it is troubling. If we’re not careful, the appearance of unfairness may cause us to reject the favorable along with the unfavorable. Or to use an idiomatic expression, “to throw the baby out with the bathwater.” Perceived unfairness deals us a major body blow.  The base isolator for unfairness is to develop faith in Jesus Christ and His atonement and understa

The base isolator for unfairness is to develop faith in Jesus Christ and His atonement and understa