When Good Intentions Breed Perfectionism

It seems many of us, as parents, want the best for our children. We want them to succeed in school, in activities, in callings, in life. We want them to become the people Heavenly Father created them to be. But sometimes, in our zeal to help them succeed—or in our own need for validation—we may unintentionally sow the seeds of something dangerous: toxic perfectionism.

As was recently described in a Y Magazine article entitled “The Perfect Problem,” parents who hold high, inflexible expectations and who respond to unmet standards with criticism or disappointment—and sometimes even withdraw love, affection, or emotional closeness—can contribute to a mindset in their children that equates worth with flawless performance.

Children are perceptive. As one researcher quoted in that article put it, they are “very sensitive to any parental fear. A sense that Mom’s afraid I’m not enough … I’m insufficient—children are going to be sensitive to that, because their safety as a person depends on the security of that relationship.”

When that becomes the “soil” in which a child’s identity grows, mistakes and developmental missteps can start to feel existential—not just as “I messed up this time,” but “I’m not good enough,” “I don’t belong,” or even, “God can’t love me if I’m not perfect.”

In the context of a family, this is especially poignant. Our faith teaches us to “be ye therefore perfect” (Matt. 5:48). Yet we also know, through the gospel of Jesus Christ, that perfection is ultimately a gift of grace, not the result of flawless performance.

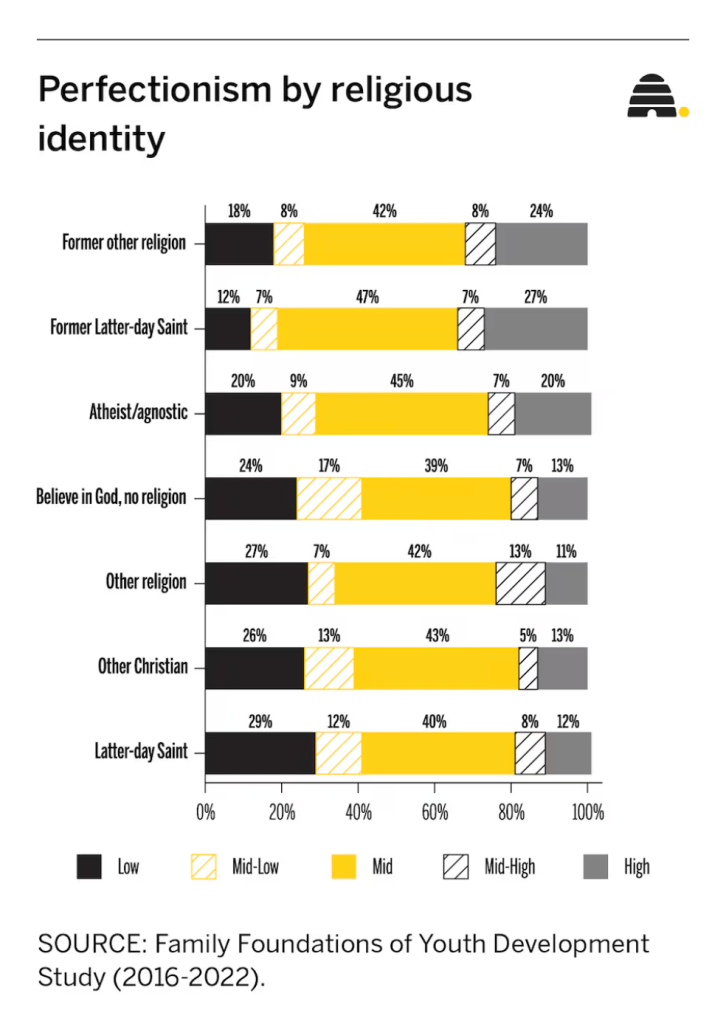

Thus, without healthy grounding in grace and identity in Christ, a home that unintentionally elevates performance—grades, callings well done, “righteous living,” temple attendance, activity in the Church—can become a breeding ground for perfectionism that undermines spiritual and emotional well-being.

It’s not just anecdotal or spiritual concern; psychological research confirms that children often pick up perfectionistic tendencies from their parents and their parenting style.

In a study of 119 children (average age about 11.7) and their parents, researchers found that children’s levels of perfectionism often mirrored their parents’. This supports what is called the “Social Learning Model.”

The same study showed that parenting style matters: when children perceived their parents as authoritarian—rigid rules, high expectations, controlling or overly critical—they were more likely to develop maladaptive/perfectionistic patterns (worry, harsh self-criticism, fear of failure) rather than the healthy striving toward excellence that might be positive.

Additional research suggests that more positive parenting—warmth, responsiveness, acceptance—is associated with healthier child adjustment. In fact, parents with “positive perfectionism” (high standards + healthy attitudes) tend to report more acceptance in their child-rearing. In contrast “negative perfectionism” (self-criticism, fear of failure) correlates with more criticism or permissiveness in parenting.

In other words: it’s not just what you expect, it’s how you expect it, how you respond when expectations are unmet, and whether love, acceptance, and identity are tied to performance.

As people of faith, we have a unique vantage. On the one hand, we believe in personal growth, striving to become more like the Savior, improving ourselves spiritually, mentally, physically, and in service. Those are good and worthy goals. On the other hand, our doctrine teaches humility, reliance on the Atonement, grace, mercy, and repentance—recognizing our mortal weaknesses and the need for divine help.

Thus, when parenting, the gospel invites us not only to encourage growth but also to foster a secure identity rooted in God’s love, not in performance metrics.

When our children learn that their worth is unchanging because they are beloved sons or daughters of Heavenly Parents, and that growth is a process, not a demand for perfection, we help inoculate them against the toxic perfectionism described in both the Y Magazine article and psychological research.

Here are practical principles, some do’s and don’ts for helping children develop healthy striving instead of perfectionism:

Do: Emphasize growth, not just results.

Encourage children to set goals, but talk with them about flexibility. Let them help define the goal, why it matters to them, not just to you. Let them see progress, even if slow. This aligns with the guidance from BYU researchers: ask “What are you learning?” instead of always “What grade did you get?” Celebrate effort, incremental improvement, and personal growth, not just top performance.

Do: Separate identity from performance.

Repeatedly reassure children that their worth is not defined by grades, talents, callings, or how many “boxes they check.” Teach them (and model yourself) that making mistakes does not make you less beloved, less worthy, or unworthy of love and forgiveness.

Do: Respond with love, empathy, and support, especially when they fail.

When a child doesn’t meet expectations or fails, respond with patience, kindness, and encouragement. Let them know you still love them, regardless of the outcome. This helps prevent a perfection-oriented mindset where mistakes equal worthlessness. Use failures as opportunities to talk about learning, growth, and reliance on Christ, repentance, and grace.

Do: Cultivate an atmosphere of security, not conditional love.

Be mindful of the emotions children read. Anxiety, fear, or disappointment from parents can communicate a sense of “If you fail, I’m afraid you’re not enough.” Parents who recognize this can help preserve a child’s sense of identity and worth. Help children understand they are children of God, loved and valuable, no matter their accomplishments.

Don’t: Tie love or approval to results.

Avoid sending messages like “I’ll be proud of you only if you succeed,” or “You’d better get straight A’s or you’ll disappoint me.” Those can create emotional insecurity that breeds perfectionism. Don’t withdraw emotional support, affection, or closeness in response to failure or unmet expectations.

Don’t: Make unrealistic or inflexible expectations the norm.

Avoid placing rigid “shoulds” on children, for example: “You must be the best,” or “You must follow this path because I want you to.” That restricts their freedom to discover their own talents and divine potential. The Y Magazine article warns that high, inflexible expectations “restrict their ability to choose their path and develop their innate talents.” Don’t treat mistakes as identity failures. Resist the all-or-nothing mindset that equates anything less than “perfect” with “worthless.”

Don’t: Confuse healthy goals with toxic perfectionism.

Having high standards isn’t wrong, but expecting perfection, punishing mistakes, or defining self-worth by achievements is where it becomes harmful. Don’t ignore signs of distress: anxiety over failure, panic at getting less-than-perfect results, or excessive fear about disappointing parents. These can be early indicators of perfectionistic patterns.

As members of the Church, we know that mortal life is a process. We are commanded to “be perfect,” but that commandment is given in the context of love, mercy, and repentance, not as a demand for human perfection. True perfection comes through the Atonement of Jesus Christ.

If we, as parents, anchor our children in that truth—that their worth is inherent, as children of Heavenly Parents; that their identity is secure in divine love; that mistakes are opportunities to learn, repent, and grow—we help them develop healthy striving, not soul-crushing perfectionism.

When we model humility (by admitting our own mistakes), repentance, reliance on Christ, empathy, and unconditional love, we teach them, not just by words, but with our lives, that they are precious, divine, and eternally loved, no matter their earthly performance.

In doing so, we help them grow into resilient, faithful disciples, not inflexible perfectionists.